The "Day the Music Died" A Technical & Cultural Pivot

The crash on February 3, 1959, often called "The Day the Music Died," is a pivotal moment because it represents a "shattering of the glass" for an earlier generation.

It was a moment where the vibrant, high-energy optimism of the 1950s met a cold, technical failure in a snowy cornfield in Clear Lake, Iowa.

This day isn't just a music history post; it's about the vulnerability of icons and the sudden end of a creative era.

I wasn’t around when this happened. I would arrive years later. When Don McLean’s American Pie came out in 1971, I just thought it was just a long song. It was melodic and had some weight to it, but I didn’t know what. Sort of like Gordon Lightfoot’s The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald. My dad explained what happened and who each of the musicians were. As I got older and more musically aware and developed my own tastes, I realized that Holly and Valens also influenced by their style.

Then there was the bio-pics in the 1980s. And as I typically do, it was a launching point for me to really investigate the each of them. I was greatful to my dad for sharing what happened, but how it affected him, as he was just a teenager at the time. I think, if anything, that made me realize that my dad and I had something in common now.

The Event: Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and J.P. "The Big Bopper" Richardson died when their chartered Beechcraft Bonanza crashed shortly after takeoff.

From my perspective: These were young men—Holly was only 22—who were actively reinventing the "system" of popular music. Holly was a pioneer in the studio, experimenting with double-tracking and orchestration long before it was standard.

The Technical Failure: Like the Challenger, this was a case of human and mechanical systems failing under environmental pressure. The pilot, Roger Peterson, was young and likely struggled with the "Sperry Gyroscope" (an attitude indicator) in the dark, wintry conditions.

Incident Brief: February 3, 1959

Often cited as the first major collective trauma of the rock-and-roll era, the loss of Holly, Valens, and Richardson represented more than a tragedy—it was a technical and cultural "hard reset" for the music industry.

| The Aircraft | 1947 Beechcraft Bonanza 35 (N3794N) |

| The Personnel | Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, J.P. Richardson, Roger Peterson (Pilot) |

| Technical Factor | Instrument disorientation (Spatial Disorientation) in a snowstorm. |

| The Legacy | The end of the "Winter Dance Party" tour and the birth of the 1960s musical evolution. |

The Winter Dance Party Trio: Three Visions of the Future

1. Buddy Holly: The Studio Architect

Buddy Holly wasn't just a singer; he was one of the first true "total filmmakers" of the music world.

The Music Style: He pioneered the standard rock band lineup (two guitars, bass, and drums) and combined country, gospel, and R&B into a clean, melodic sound.

Professional Innovation: In the studio, Holly’s mind was always racing. He was obsessed with technical craft, experimenting with double-tracking his vocals and using celesta and orchestral strings—techniques that would later become the blueprint for the Beatles.

Personal Life: At 22, he had recently married Maria Elena Santiago and moved to Greenwich Village to immerse himself in the jazz and poetry scene. He was a businessman who had just broken away from a restrictive management deal to take full "administrative" control of his career.

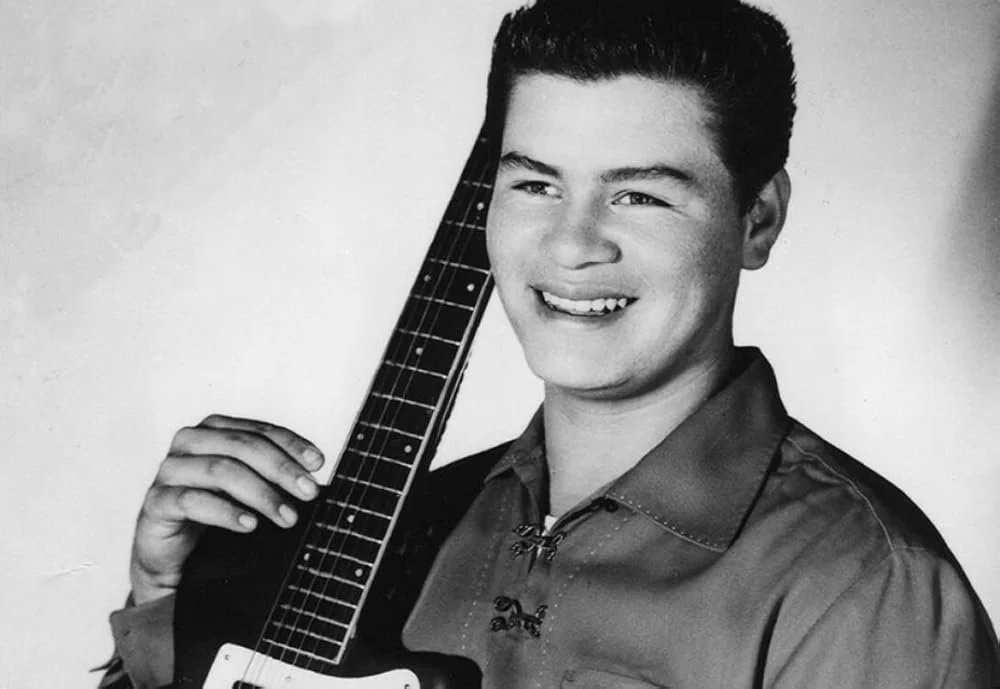

2. Ritchie Valens: The Cultural Bridge

Valens was a prodigy who, in a career lasting only eight months, fundamentally changed the American soundscape.

The Music Style: A pioneer of Chicano Rock. He infused traditional Mexican folk music with high-energy rock and roll.

Professional Impact: With "La Bamba," Valens proved that a non-English song could dominate the U.S. charts. He brought a raw, garage-band energy to the "system" of pop, playing his own guitar leads with a rhythmic intensity that foreshadowed the surf-rock era.

Personal Life: Only 17 years old at the time of the crash, Valens was a kid from Pacoima, California, who had a deep fear of flying due to a childhood trauma involving a plane collision over his school. He famously won his seat on the Beechcraft Bonanza via a coin flip—a chilling example of how a split-second variable can change history.

3. J.P. "The Big Bopper" Richardson: The Media Persona

Richardson was a man who understood the "Marketing and Promotion" side of the industry better than almost anyone in 1959.

The Music Style: His style was "Novelty Rock"—performative, loud, and built for the burgeoning world of radio and television.

Professional Innovation: Before the tour, he was a legendary Texas DJ. He actually coined the term "Music Video" in 1958 and recorded several filmed performances intended for a "jukebox" that would play movies. He also held the world record for continuous broadcasting (six days and nights).

Personal Life: At 28, he was the "elder statesman" of the flight. He was a family man with a pregnant wife at home. He only took the seat on the plane because he was suffering from the flu and hoped to get to the next venue early to rest and do laundry—a mundane, human decision that led to a monumental loss.

Technical Summary: The 1959 Personnel File

Legacy Profile: The Winter Dance Party Personnel

| Artist | Core Innovation | Industry Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Buddy Holly | Studio Overdubbing & Orchestration | Established the 4-piece "self-contained" rock band model. |

| Ritchie Valens | Cultural Synthesis (Latin/Rock) | First major Chicano star to break the English-language chart barrier. |

| The Big Bopper | Visual Media Concept (Music Videos) | Pioneered the concept of recorded visual performances for promotional use. |

Buddy Holly isn’t just a singer—he’s a Technical Disruptor. In 1957, the electric guitar was still a new, misunderstood machine. Holly was the first "operator" to show the world exactly what a solid-body electric guitar could do as the lead engine of a band.

Technical Spotlight: The Stratocaster Shift

The Machine: The 1954/55 Fender Stratocaster

When Buddy Holly appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1957, most of America had never seen a Fender Stratocaster. It looked like something out of the sci-fi books your father bought you—contoured, futuristic, and finished in a "Two-Tone Sunburst."

The Design: Unlike the heavy, hollow-body jazz guitars of the era, the Stratocaster was a solid-body tool. It was built for endurance and clarity, not warmth.

The Pickup Configuration: The three-pickup system allowed Holly to achieve a "percussive" and "jangly" tone that cut through the mix. This became the signature sound of early Rock and Roll.

The Synchronized Tremolo: Holly used the vibrato bridge to add "shimmer" to his chords, a technical flair that made his music sound like it was vibrating with energy.

The Influence: Engineering the British Invasion

Buddy Holly was a direct influence across the Atlantic—specifically in Liverpool and London. To young musicians like John Lennon, Paul McCartney, and Keith Richards, Holly wasn't just a star; he was a blueprint.

The Self-Contained Unit: Before Holly, stars were usually frontmen backed by an orchestra or a rotating door of session players. Holly and The Crickets showed the British Invasion bands that a four-piece "self-contained" unit (two guitars, bass, drums) could produce a massive, professional sound.

The Songwriting Logic: Holly wrote his own material. This encouraged The Beatles and The Rolling Stones to stop being just "performers" and start being "creators" of their own systems.

The Visual Branding: Holly proved that you didn't have to look like an untouchable "Adonis" like Elvis. You could be a guy with glasses and a technical-looking guitar and still dominate the world.

Hardware Profile: Holly’s '55 Stratocaster

| Body Construction | Solid Ash with "Deep Contour" shaping for ergonomic performance. |

| Electronics | Three Single-Coil Pickups; staggered pole pieces for string-to-string balance. |

| The "V-Neck" | Maple neck with a pronounced V-shape, facilitating faster chord transitions. |

| Legacy Impact | Directly inspired Eric Clapton, George Harrison, and Hank Marvin to adopt the Stratocaster. |

The Architect vs. The Engine: Holly and Valens

Buddy Holly: The Methodical Architect

Holly’s approach to songwriting was technical and layered. He viewed the song as a construction project.

The Logic: He used clean, mathematical chord structures (I-IV-V) but enriched them with clever rhythmic hiccups (the "hiccup" vocal style).

The Innovation: Songs like "Words of Love" and "Everyday" showed his obsession with the "clean" sound. He wasn't afraid of quietness; he used it to build tension. His work was about precision.

Ritchie Valens: The High-Octane Engine

Valens, on the other hand, was the master of raw kinetic energy. He brought the "garage" spirit to the professional stage.

The Logic: "La Bamba" is a technical marvel of a different kind—it’s built on a repetitive, driving riff that doesn't let go. It was a three-chord loop that felt like an unstoppable force.

The Innovation: Valens brought a "distorted" feel to his performances before distortion was a standard pedal. His energy was about impact. He didn't want the listener to analyze the song; he wanted them to feel it through the floorboards.

Technical Comparison: The Architect vs. The Engine

| Design Feature | Holly (The Architect) | Valens (The Engine) |

|---|---|---|

| Compositional Logic | Methodical layering, sophisticated chord shifts, and studio overdubbing. | Raw kinetic energy built on driving, repetitive riffs and cultural synthesis. |

| Sonic Aesthetic | "Clean" clarity, "jangly" tones, and orchestrated precision. | "Garage" intensity, high-volume impact, and percussive vocal delivery. |

| The "Hook" Strategy | Technical vocal "hiccups" and melodic flourishes. | The relentless, hypnotic "La Bamba" guitar loop. |

| Industry Legacy | Established the blueprint for 1960s Pop-Rock and Studio experimentation. | Pioneered the foundations of Latin-Rock and early Punk energy. |

The tragedy of February 3, 1959, is that it stopped two very different machines at the exact moment they were hitting their stride. Holly was about to enter his "experimental" phase in New York, and Valens was just beginning to show how Mexican folk could be weaponized into rock and roll.

They were the two halves of the modern musician: the Technical Designer and the Raw Powerhouse.