The Centennial Eve: Why Fritz Lang’s 'Metropolis' Still Defines Our Future

As we enter the second week of January 2026, we are officially one year away from the centenary of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, which premiered in Berlin on January 10, 1927. While it is nearly a century old, the film’s influence on entertainment, architecture, and our understanding of society remains unparalleled.

Lately, I have been looking at how film, philosophy, and society intersect. Metropolis is the ultimate case study. It isn't just a relic of the silent era; it is the blueprint for the modern dystopian epic.

The Technical Foundation: The Schüfftan Process

Before the advent of CGI or even sophisticated matte paintings, Fritz Lang had to solve the problem of scale. He utilized the Schüfftan process, a technique using specially curved mirrors to place live actors into miniature sets.

This allowed Lang to create a vertical city that felt immense and oppressive. When you look at the towering skylines of Blade Runner’s Los Angeles or the multi-level city of Coruscant in Star Wars, you are seeing the direct DNA of Metropolis. Lang didn't just film a story; he invented the visual language of the "City of the Future."

The Machine-Human: A Century of AI Ethics

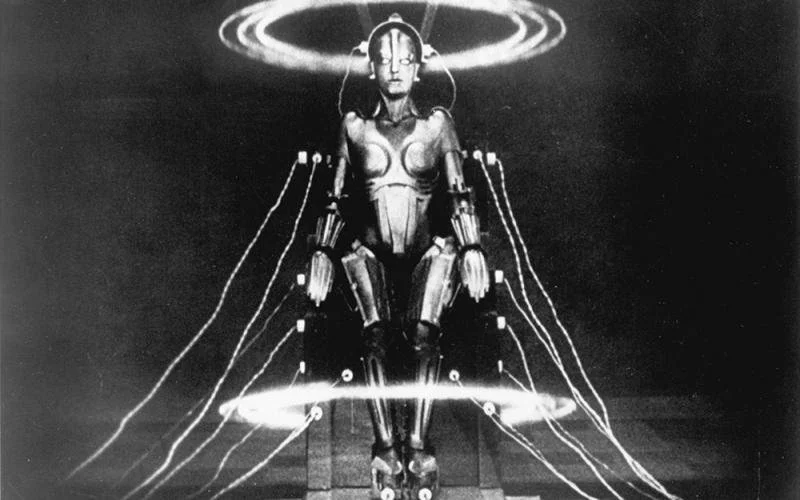

Perhaps the most enduring image from the film is the Maschinenmensch—the robot created by the scientist Rotwang to replace the revolutionary leader Maria.

This was the first time a robot was depicted as a central character in a feature film. Philosophically, it raised questions that we are still grappling with in 2026:

The Ethics of Replacement: Can a machine truly replicate a human’s influence on society?

The "Mad Scientist" Archetype: Rotwang established the trope of the creator obsessed with his creation, a theme that flows through Frankenstein, Ex Machina, and modern discussions on AI development.

The Philosophical Core: The Head, the Hands, and the Heart

The film’s screenplay, written by Thea von Harbou, centers on a specific societal philosophy: "The Mediator Between the Head and the Hands Must Be the Heart."

In the context of the film, the "Head" represents the thinkers and planners (the elite), while the "Hands" represent the workers who keep the city’s massive machinery running. Lang’s warning was that without the "Heart" (empathy and mediation), the friction between these two classes would lead to total societal collapse. In 2026, as we discuss the "Great Divide" in labor and the rise of automation, this 1927 thesis remains strikingly relevant.

Metropolis Impact Snapshot

As we approach the 100th anniversary in 2027, Metropolis stands as a reminder that the best science fiction doesn't just predict technology—it predicts the human condition.

When Metropolis premiered in 1927, it didn't receive the universal praise we might expect for a "masterpiece." Instead, it was a lightning rod for controversy. Critics were stunned by its technical visuals but deeply divided—and often quite harsh—regarding its social and political messages.

For your blog post, including these original reactions adds a layer of historical perspective that shows how the film’s "soft-headed" philosophy was viewed long before it became a cinematic legend.

1927 Critical Reception: Technical Marvel vs. "Philosophical Bunkum"

The most famous (and most scathing) review came from H.G. Wells, the father of science fiction himself. Writing for The New York Times, Wells was not impressed. He called it "the silliest film" ever made, attacking what he felt was a "muddlement about mechanical progress."

The H.G. Wells Critique: Wells argued that the film’s central premise—that machines turn men into exhausted drudges—was scientifically and economically backward. He believed automation would relieve drudgery, not create it. To him, the film was a "soupy whirlpool" of clichés.

Mordaunt Hall (NY Times): Hall famously described the film as a "technical marvel with feet of clay." He praised the "extraordinary" art direction but found the story "immensely and strangely dull" and the characters lacking rational motivation.

The Political Crossfire: In Germany, the reception was even more complicated. The film was accused by some of spreading communist rhetoric because of its depiction of class revolt. Simultaneously, others (including later critics like Siegfried Kracauer) argued the film’s "Mediator" resolution actually leaned toward fascist ideology by suggesting classes should simply "shake hands" and maintain their existing roles rather than actually equalizing power.

Contemporary vs. Modern Perspective

Historical Reception: The 1927 Reviews

"It gives in one eddying concentration almost every possible foolishness, cliché, platitude, and muddlement... served up with a sauce of sentimentality."

— H.G. WELLS (The New York Times)"A technical marvel with feet of clay... adroitly spliced together but often simplistic."

— MORDAUNT HALL (The New York Times)"Accused of pushing the communist line while simultaneously admired by those who would later lead the Nazi party."

— HISTORICAL CONSENSUS (Weimar Republic)Why i think the Critics Were (Half) Wrong

While the 1927 critics were right about the plot being "myth-like" and "simplistic," they failed to see that this simplicity is exactly what allowed the film to endure. By using archetypes—The Mad Scientist, The Savior, The Machine-God—Lang created a modern myth that could be re-interpreted by every generation.

H.G. Wells looked for scientific accuracy; modern audiences look for the human soul trapped within the gears of progress.

My thoughts on How to Experience 'Metropolis' in 2026

If you are new to silent film, Metropolis can be a daunting prospect. It is long, stylized, and utilizes acting techniques (Expressionism) that are far more theatrical than modern performances, think Nosferatu (the original). Here is how to get the most out of your first viewing:

Seek the 2010 Restoration: For decades, nearly a quarter of the film was missing. In 2008, a nearly complete 16mm print was discovered in an Argentine museum. The 2010 "Complete Metropolis" restoration is the gold standard, providing the most coherent narrative structure.

Watch for the Visual Symmetry: Lang used a highly structured visual style. Notice how the workers move in rigid, machine-like patterns compared to the chaotic, fluid movements of the elites in the "Yoshiwara" nightclub. The film tells its story through movement as much as it does through title cards.

The Soundtrack Matters: Since there is no dialogue, the music is your emotional guide. The original Gottfried Huppertz score is magnificent, but for a different vibe, many enjoy the 1984 Giorgio Moroder version, which features 80s pop icons like Freddie Mercury and David Bowie.

Pro-Tips for Your First Viewing

- 01 Look for Expressionism: The exaggerated facial expressions and shadows aren't "bad acting"—they are a specific art style meant to project internal emotions onto the external world.

- 02 Observe the Architecture: Pay attention to how the buildings dwarf the characters. This "Vertical City" design was meant to show the insignificance of the individual compared to the state.

- 03 Note the Biblical Imagery: The "Tower of Babel" and the "Moloch" machine sequences are not accidental; Lang was using ancient myths to explain modern industrial anxieties.

Final Conclusion: The Road to 2027

As we count down to the 100th anniversary next year, Metropolis remains a vital piece of our cultural vocabulary. It challenges us to consider if our "Head" and our "Hands" are still in conflict, and whether we have found the "Heart" necessary to manage the technology of our own era.

Whether you watch it for the historical significance or the sheer visual audacity, you are witnessing the birth of the future.

The Modern Echo: A Discussion for the Comments

When we look at Metropolis at 99, we aren't just looking at the past; we are looking at a mirror. From the sleek halls of Westworld to the rain-soaked streets of Blade Runner, the "City of the Future" is still being built on Fritz Lang’s foundations. But the question remains: have we actually moved past the conflict of the "Head" and the "Hands," or have we just added more layers of technology to the struggle?

I want to hear your thoughts on how this 1927 vision fits into our 2026 reality.

Discussion Questions:

The AI Ancestry: Does the Maschinenmensch feel more like a warning or a prophecy given the state of modern robotics today?

The Architect's Vision: If you were to design a "Metropolis" for the 21st century, would it still be a vertical city, or has the digital age made geography irrelevant?

The "Heart" Logic: Was Lang right? Can a "mediator" actually bridge the gap between social classes, or was H.G. Wells correct to call it "philosophical bunkum"?

Join the Conversation

What’s Your Dystopia?

From 1984 to The Last of Us, every generation has a story that warns us about the future. Which one keeps your mind racing the most?

Drop a Comment BelowDon't forget to subscribe for more deep dives into the films that shaped our world.

The Metropolis Genealogy: A Watchlist

To see how Fritz Lang's 1927 vision fits into modern cinema, watch these in order:

- Blade Runner (1982): For the vertical architecture and class decay.

- Dark City (1998): For the Expressionist shadows and city-shifting mechanics.

- Ex Machina (2014): For the modern evolution of the Maschinenmensch.